Firearms

NotOpodcast: Episode 4

Welcome to the fourth episode of NotOpodcast, where Kilroy and Michael join me to discuss a variety of topics such as the Pokemon GO craze, smartwatches and augmented reality, self driving cars, some background on the AR15, and the "One Gun" philosophy.

The timecodes are:

Gaming - 0:40 - Pokemon GO, Nintendo

Technology - 20:40 - Wearables, Self Driving Cars

Firearms - 36:38 - History of AR15, One Gun Philosophy

NotOpodcast: Episode 3

Welcome to the third episode of NotOpodcast, where Kilroy and Michael join me to discuss a variety of topics such the latest on E3 announcements from this week, physical phone keyboards, an in depth look at the upcoming Xbox Project Scorpio, the tactical triad, and ignorance about AR15s.

The timecodes are:

Gaming - 0:45 - E3, Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo

Technology - 35:23 - Physical vs Software Phone Keyboards, Xbox Project Scorpio Specs

Firearms - 54:15 - Tactical Triad, Michael Moore AR15 Tweet

ZAUF: Types of Rifles

Earlier in this series, we established the separation of firearms into three very broad categories: rifle, shotgun, and handgun. Each firearm category has its own purpose and role to play in the spectrum of usage. Let’s continue by taking a more granular look at the different types of rifles.

The rifle category is defined by the lands and grooves carved down the interior length of the barrel, as well as the fact that the weapon is meant to be fired from the shoulder. These lands and grooves, called “rifling”, serve to impart a spin upon the projectile as they leave the weapon, making it more accurate at distance with the proper projectiles.

In the broadest sense, the category of rifle is broken down by specific types of actions: e.g. bolt action, lever action, pump action, semi-automatic, and various types of single shot. In the current civilian market, the most popular rifles are generally within either the bolt action or semi-automatic category. Further expanded, rifles are also split up by their purpose, with common categories including hunting, sniping, assault, battle, and other terms entrenched in common parlance. These terms will be further explored in a future ZAUF article.

Bolt action rifles are defined by their action; a manually operated bolt that is opened and closed to cycle a cartridge in and out of the chamber. Bolt action rifles may be loaded with an internal or external magazine, and may come in the form of single shot rifle with no form of additional feeding. Variations of the bolt action operation usually come in the type of handle the bolt uses: left, right, or straight pull. Because of the particular way bolt action rifles operate, along with the greater overall strength of the mechanism, this type of rifle is able to reliably handle much larger and more powerful cartridges than other types of action.

Lever action rifles are defined by the lever, usually wrapped around the trigger guard and grip of the firearm, which is used to cycle the action. This style of action is not as strong as its bolt action counterparts and suffers, generally, from an in-line magazine which runs underneath the barrel. The particular quirk of this type of firearm means that most lever action rifles, unless fed by a box magazine, will only be available in calibers with flat-nosed or round nosed bullet loads in much lower overall strengths. This is because sharper nosed bullets line up in a tube have the unfortunate possibility of accidentally setting off the primer from an adjacent round.

Pump action rifles use a pump to cycle the cartridge through the rifle in the same manner as a pump action shotgun. This type of action generally uses the same under-barrel linear magazine as their lever action brethren, though there are models which utilize a detachable box magazine. This type of action tends to be rarer in the rifle category than it is in the very common pump action shotgun category.

Semi-automatic rifles are defined by their action self-loading the next available round through various means of recycling the energy created by firing a round, as well as by the fact that they fire only a single round every time the trigger is pulled. This is the key that differentiates a semi-automatic rifle from a fully-automatic rifle, as the latter is capable of sustained fire from an ammunition source with only one pull of the trigger. This category of rifle covers a very broad range of firearms available historically, as well as in contemporary production. Earlier historical examples tend to be fed via stripper clip into a fixed internal magazine, while modern production semi-automatic rifles generally opt for a removable box magazine for feeding.

Finally, more niche single shot rifles come in a variety of actions such as break action, falling block, and various types of muzzle loaded rifles. Break action rifles are generally single or dual-shot firearms that are loaded by breaking open the action at the breech (toward the stock) end. Cartridges in break action rifles are loaded and removed by hand with some amount of spring assistance. A falling block action is generally actuated by a lever underneath the action (usually wrapping around the trigger guard), but requires manual action to extract and load any following rounds. Finally, muzzle loaded rifles hearken back to the days of the musket wherein powder, wad, and shot are loaded from the muzzle (business end) of the rifle and jammed back into the breech. Modern black powder muzzle loaders continue to remain popular for hunting.

This provides general overview of the types of rifles in some broad subcategories separated by their action types. There are many more distinctions that are available amongst rifles that will be covered later on.

Buyer's Guide to the 1911

Welcome to our buyer's guide to the 1911. If you're not interested in a long winded in-depth guide and just want an immediate and basic recommendation, buy an $650-$1200 pistol chambered in .45 ACP with a Government length (5”) barrel from Springfield Armory, Colt, Smith & Wesson, SIG Sauer, Ruger, or Remington. The decision between each of those models and manufacturers will come down to price and preference.

History

For the uninitiated, the M1911 pistol has been in continuous service with the United States Armed Forces since the year 1911 (hence the name), when it beat out the Luger pistol chambered in 9x19mm Parabellum for the initial contract. It has provided over one hundred years of continuous service internationally to date, and by the looks of things, it will continue to do so for some time. The important names which you’ll hear talked about surrounding this particular pistol are John Moses Browning and Samuel Colt, two industry legends.

Both the design and designer of the 1911 have a well-deserved reputation, with John Browning having been granted 128 firearms patents in his lifetime. Arguably, the 1911 was and still is his largest success in the firearms industry. Although, a number of his other designs such as the Hi-Power (GP35), M1919 machine gun, and the M1917 machine gun will hit their centennials relatively soon and are also well regarded firearms.

On the other hand, Samuel Colt, of the famous quote “God made man, but Sam Colt made them equal.” was actually quite dead by the time the M1911 was designed, having passed away in 1862, when John Browning was 7 years old. Instead, the credit for the fame of the “Colt 45” goes to his company, which was awarded government contracts for the production of a number of different firearms over the course of US history, including a new order as of July 2012 for more of the M1911 pistols.

The M1911 design has seen both World Wars, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the current conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, and a myriad of other battles locally and abroad. It’s no wonder that anyone would be interested in having their own piece of history, making the M1911 a very popular pistol. For the average consumer, choosing a 1911s is a fairly large quandary, with almost every company producing their own flavor of the classic pistol, with a variety of options and customizations, each of which may suit some people better than others.

Before continuing, as a point of note, when I refer to the platform as the 'M1911' or simply the '1911', what I truly mean is the M1911A1 and its modern derivatives. The original M1911 was modified with some small external changes in 1924 and was designated the M1911A1, although the longer title has never really entered common colloquialism.

What To Expect

When opting for a 1911, you’re buying a 100 year old design. This does not mean the design itself is irrelevant or bad, merely that it will take a certain approach and recognition of inherent flaws in the design when it comes to maximizing the utility of the weapon.

Caliber Introduction

The modern 1911 platform comes in a variety of calibers, ranging from the standard ‘Big Three’ to more specialized calibers that have not been widely adopted and probably require a reloading setup to take advantage of. In this section I’ll be summarizing both the popular cartridges available for the design as well as some of the newer, boutique ones for more niche purposes. All magazine comments are geared toward people buying the single stack 1911 models, since the various double stack models have their own quirks and differences.

- .22LR (Long Rifle): A very handy training cartridge, this round is widespread and generally fairly cheap to acquire. There are 1911s chambered in .22LR as well as .22LR conversion kits for 1911s that modify the barrel and internal parts to account for the lower pressure and operating force of this cartridge. There are also .22LR pistols designed to look like a 1911 on the outside, but have even more significant differences in the internal workings and will operate differently than a 1911 chambered in .22LR.

- .45ACP: The cartridge the 1911 was originally designed for, this venerable round has been in service since the introduction of the handgun more than a century ago. Ballistics-wise, this cartridge is big and relatively slow. However, the in-depth discussion of it in relation to the rest of the ‘Big Three’ is a discussion for another day, though for a short introduction, you can check out our discussion of the ‘Big Three’ in our ZAUF series. In terms of magazine capacity, the original standard was seven rounds, with more modern standards set at 8, or if one is willing to use an extended magazine, 10. Of note, however, is that in a traditional 1911 chambered in .45 ACP, constant chambering and rechambering of the same round will result in bullet setback - when the bullet itself is pushed deeper into the brass from where it was originally seated. Cartridges suffering from bullet setback are dangerous to fire and should be removed from use.

- .45 Super: A cartridge design based off of the .45 ACP, .45 Super has the same external measurements, but with thicker walled brass that is loaded to higher pressure specifications, making it a more powerful round. Some, but not all, 1911s that are chambered in .45 ACP are also rated for .45 Super firing. It is up to the owner to check with the individual manufacturers to see if their 1911 is rated to handle .45 Super.

- 9x19mm Luger/Parabellum: With the rise in popularity of the cartridge itself as well as the adaptation of the M1911’s design, the 9mm cartridge works well on the platform and has been adopted in wider use by competition shooters and people looking to shoot a different caliber out of the 1911 platform. Magazine capacity for a standard 9mm model is about 10 rounds in a flush fit magazine, and more for extended magazines. In the author’s opinion, if you want a 9mm pistol and a Browning design, buy a Hi Power.

- .38 Super: A popular competition cartridge that traces its roots back to a drawing board in Colt’s factory, this cartridge is actually surprisingly powerful for the amount of attention it doesn’t receive. Ballistically, when using the right loads this cartridge overpowers 9mm Luger and can give .357 SIG a run for its money. If you’re buying a gun in this cartridge, you probably don’t need me to tell you how great it is. Good luck in IPSC.

- .357 SIG: This caliber is great - a solution to a problem that may or may not have existed - and has been adopted by a number of agencies including the Secret Service. However (and this is a rather large ‘however’), I do not believe the .357 SIG has any place in serious use with an M1911. With the .40 casing, this caliber only offers an absolutely minimal magazine capacity increase when compared to .45 ACP. It can also present issues caused by the necked casing. In short, if you want a gun in .357 SIG, the 1911 is not the best option.

- .40 S&W: A fairly popular cartridge used by law enforcement after the FBI decided 10mm was too powerful for them, this cartridge has a reputation of being a legitimate compromise between 9mm and .45ACP while also being Short(er) and Weak(er) than its 10mm parent cartridge (in all seriousness, the S&W stands for Smith & Wesson). From a practical standpoint, while you can buy a gun in this caliber, I never recommend it.

- 10mm: An interesting cartridge designed by Col. Jeff Cooper (who deserves a discussion in another article) in an effort to transcend the original pitfalls of the .45 ACP cartridge. This particular cartridge shoots flatter, farther, and is more powerfully than any of the ‘Big Three’ at the cost of increased recoil and in the current market, being significantly more expensive to purchase. So if you want a 1911 in 10mm, be sure you can handle the recoil, and be prepared to pay the price of ammunition.

- 7.62x25mm Tokarev: Actually a fairly rare find, there are conversion kits available for 9mm caliber M1911s that involve changing out the entire upper assembly (slide, barrel, bushings, etc.) and magazine to accept the elongated Russian ammunition. 7.62x25mm Tokarev is fast and cheap, so if the cost of ammunition is a concern, it might be worth considering.

- .400 Cor-bon: A more modern innovation focused on getting the ballistics of 10mm while still using the .45 ACP brass. This is a wildcat cartridge (meaning it is not mass produced and is not necessarily readily available) and is expensive to purchase in relation to the others on this list.

- .50 GI: A very niche wildcat round that boasts a larger diameter and improved ballistics over the .45 ACP cartridge. As of this writing, it is purely a novelty that provides the satisfaction of having a larger bullet that hits a little harder.

Grip Safety

The grip safety is the lever-like protrusion at the rear of the pistol frame that is held up against the web of the firing hand and needs to be fully depressed for the pistol to fire. In theory, under stress the grip safety will be depressed because the firing hand will have an adrenaline-fueled vice grip on the pistol and won't be an issue that requires discussion. However, after over 100 years of observation, there have been a number of incidents in which someone with a hand wound was unable to make the handgun function under stress due to being unable to deactivate the grip safety. Many consider this particular pitfall of the design to be one of the major downsides of the 1911 platform.

It is of my opinion that the 1911 design is the only one that can get away with having a grip safety since modern handguns that lack the sliding trigger or the particular safety/sear combination of the original design have no reason to even consider it (looking at you, HS2000/Springfield XD.) Furthermore, the original design of the pistol lacks a firing pin safety of any sort, leaving the grip safety and manual safety as the only 'safety' features on the firearm. The 1911 is a single action handgun, meant to be carried 'cocked and locked', meaning that the hammer is locked back and there is a round in the chamber.

The grip safety, the manual safety, and not pulling the trigger are the triad of conditions preventing the firearm from being negligently discharged. As a worst case scenario, if the manual safety lever is deactivated, the grip safety and absence of trigger pull are still there to prevent the gun from firing. Removing the grip safety from the single action only design only increases liability and potential hazard of misuse.

The single action only configuration is the confounding factor, with even some of the more poorly made 1911s having a relatively light and short trigger pull. That tradeoff is made for exactly those reasons, without the longer and heavier trigger characteristics of a modern design, the individual operator is able to shoot the pistol more precisely and consistently than its competitors.

Controls

As stated above, the original design of the 1911 comes with a manual safety lever that must be flipped down to fire the weapon. This safety lever interacts with the sear and hammer assembly to physically prevent the movement of the trigger to the rear as well as preventing the hammer from falling onto the firing pin. The original design of the lever is rather small and many modern designs have improved upon it with extended safety levers as well as adding the option to also have a lever on the right side of the pistol to make the weapon suitable for ambidextrous use. As a personal recommendation, unless you want a true to life replica of the older designs, the extended safeties are worth every additional penny.

Barrel

The M1911 bears a slightly different terminology when it comes to the size of the frame and length of the barrel between different models. It is understood if you refer to the different sizes by their more universal terms such as 'Full size', 'Compact', and 'Subcompact', but the specific vocabulary for the M1911 is as follows:

- Long Slide: Generally a barrel 6 inches or longer with a full sized frame, these are aptly named because these particular models generally have a custom made slide to cover the additional barrel length. This particular barrel length is significantly more common in competition circles and Arnold Schwarzenegger movies.

- Government: A 5 inch barrel, generally considered the 'full size' version of the 1911. This particular length is the one that was adopted for widespread service by the US Government and bears that title.

- Commander: A barrel about 4 inches long with shortened frame to match, this length is considered the 'compact' size of the M1911.

- Officer: The smallest of the lot, referring to a barrel approximately 3.5 inches long with an even more abbreviated frame. This length is considered the 'subcompact' size.

Trigger

The M1911 operates with a fairly unique trigger system uncommon in modern designs. Unlike other pistol designs, the trigger of the 1911 slides into the frame instead of hinging on a single point like a lever. This translates to a smoother, more consistently rearward trigger pull for the end user. This more 'luxurious' trigger pull benefits everyone from the most basic paper puncher all the way up to professional shooting competitors with highly tuned raceguns, which continues to drive the popularity of the platform.

Furthermore, the actual face of the trigger itself comes with various textures and geometry. The original design geometry of the trigger is slightly curved in a half moon shape, but modern innovations have different trigger geometries ranging from differently angled curves all the way to straight, flat triggers. The face of the trigger itself also ranges anywhere from smooth to serrated in various granular densities meant to give the shooter better tactile detail and control of the trigger pull.

Single Stack Magazine

The original design of the 1911 comes with a single stack magazine. (For more on magazines, see our Zen and the Art of Understanding Firearms series here.) Additionally, the original design of the magazine had feed lips optimized for the 230 grain FMJ ball ammunition that was prevalent during the time period. (For a very detailed discussion on 1911 magazines, click here).

Modern 1911 magazine feed lips come in 3 broad categories: GI, Hybrid, and Wadcutter.

- GI spec magazine feed lips are designed solely for feeding FMJ ball ammunition (for more on bullet types, check out our ZAUF article here). The lips themselves are long and tapered toward the rear, maintaining full control of the cartridge through the entire firing and feeding cycle. This particular magazine type is actually fairly rare to find aftermarket and generally will only come in the 7 round capacity.

- Hybrid spec magazine feed lips allow the cartridge to spring free of the magazine's control earlier in the feeding cycle for the purpose of improving reliability in feeding non-hardball ammunition such as hollowpoints and wadcutters. The lips themselves are generally shorter while preserving the taper of their GI derivations.

- Wadcutter spec magazine feed lips are short and parallel, designed specifically for the wadcutter problem. Testing by the source cited above has shown that these short, parallel feed lips are a way to avoid double feeds when using rounds with a shorter overall length by way of preserving the intended feeding angle coming up out of the magazine.

Internal and External Extractors

A modern issue with the 1911 platform is the current implementation of various extractors. The original design of the 1911 stipulates an internal extractor and many purists will defend that decision to the death. However, opting for an internal extractor in a modern production pistol will entail a higher price tag due to the additional cost of fitting and finishing required to properly tune an internal extractor.

For anyone with any experience with modern handguns, an external extractor is par for the course: accessible visually from the outside of the pistol, in the production of a given firearm an external extractor is much easier to deal with and doesn't add any unforeseen costs to the production of the pistol. As it is with everything, mileage varied throughout some production models with various shifts in quality and reliability throughout the years, but modern production 1911s with external extractors will generally be reliable in their function.

Full Length Guide Rod

Referring once again to the original design of the 1911, the design required only a short rod tensioned with the mainspring against the recoil spring plug. A trend in modern 1911s has been to eschew that for an 'improved' design involving a two-piece full length guide rod that requires a tool (usually a hex wrench of some variety) to remove it from the frame. What many manufacturers will promise from this change in design is an inherent increase in accuracy for the weapon. From personal experience and the majority of anecdotes available for public perusal, there is no real evidence to support that statement beyond marketing hype. As a rule, I do not recommend opting for a full length guide rod in a 1911 purchase because it will only add unnecessary complexity without any added function.

Barrel Bushings

The 1911 is fairly unique in the field of modern production handguns due to the fact that it uses a removable barrel bushing. The barrel bushing is the piece at the front of the slide that surrounds the barrel, keeping it in place during the operation of the weapon as well as providing the cap which holds in the recoil spring and plug.

A few modernized designs will instead utilize a bull barrel (which is thicker than a standard barrel) that eliminates the need for the barrel bushing but requires the full length guide rod described above.

Aside from aesthetic reasons, the only reason to acquire these particular types of modernized designs is for competition purposes, and if you’re building a racegun you probably already know what you want out of your pistol and this guide is probably too basic for your needs.

Series 70 vs Series 80 1911s and the Firing Pin Block

The original design of the 1911 did not incorporate a firing pin block. For the uninitiated, a firing pin block is a safety system that prevents the firing pin from accidentally activating on anything short of having the trigger pulled, usually at the cost of changing the actual feel of the trigger pull itself.

The colloquialism used in the subsection involves the Colt manufacturing series of 1911s, the Series 70 models being made in the original style without the firing pin block and the Series 80 being made with a firing pin block.

As with most colloquialisms, this is not an entirely accurate description of the true difference between the 70 and 80 Series of guns, but in common parlance the lack or presence of the firing pin block is enough to cover the topic conversationally. For a more in depth discussion of this topic click here

As far as the practical concerns of the firing pin block, there will be a difference in the feel of the trigger pull when there is a firing pin block present. Usually this difference is described as being heavier and grittier, getting in the way of target trigger performance. However, if you’re willing to spend the money to get a trigger job done by a good gunsmith, the presence of the firing pin block will be a non-issue. However, the firing pin block is not required by the design in order for the firearm to be considered safe, as the existing safeties and mechanics of the gun are enough to prevent an accidental discharge. The firing pin block adds another layer of safety that the individual can opt for if they like.

Controlled Feed Principle

Simply put in this write-up the cartridge must remain in full control of the pistol from the time the magazine is locked in place to when the spent casing clears the ejection port. Once again referring to the original design of the M1911 platform, with GI spec magazines and the full metal jacket ammunition that the pistol was designed to use, this principle is held true through the entire loading/firing/ejection/feeding cycles.

Modern improvements and changes simply add another (or multiple other) dimension of issues to consider during the microseconds of ejecting, feeding, and chambering. The trend away from the GI spec magazine lips takes away from the full control of the cartridge during the feeding cycle in favor of entrusting proper chambering to the forward momentum of the new cartridge rather than pressure applied during the feeding cycle.

Commercial Production

For general consumer purposes, the available firearms on the market can be separated into five broad tiers based almost entirely on cost:

- Budget: This tier is dominated by the Philippine import companies such as Rock Island Armory and American Tactical Imports. The price range starts relatively low and is capped at about $600. Many of these companies are able to provide a decent product that may have more modernized amenities and features than their higher priced counter parts by taking advantage their location and labor costs to lower their prices.

- Basic Commercial Production: This tier of production involves many commercial brands that lack the higher end features and hand fitting of their premium counterparts, but generally tend to be made in the US and come with quality guarantees as well as the custom shop capability to back their promises up. The general price range involved in this tier is anywhere from $600-$850

- Premium Production: The luxury tiers of the commercial brands, these pistols are made from the same production parts as their basic brethren but spend a brief period in each company’s custom shop for some hand fitting and finishing. The general price range of this tier will run from $850-$1200.

- Semi-Custom: Generally a very high end tier of pistol that has the option of being made to order and begin their lives entirely in the care of the company’s custom shop, these pistols receive extra care and quality control from beginning to end of their production cycle. The price range on these pistols will run generally from $1500-$3000

- Custom: At this tier, you’re no longer dealing with commercial production, but instead generally with small custom shops and individual gunsmiths. These pistols are made to order to individual specifications and requirements and exist in a tier generally from $3000+.

Building a 1911

Some people will want to take on the project of building a 1911 from ‘scratch’, or hand fitting together parts from a premade slide, receiver, and barrel kit. I cannot express how strongly I advise against this particular course of action if you have no previous machining experience. While relatively simple in theory, there is a reason why gunsmithing is considered a professional trade that requires specialized tools. For a vast majority of people, the endeavor will be filled with nothing but pain and frustration.

However, if you are completely insistent on building a 1911 from a parts kit for yourself, read this as a way of familiarizing yourself with the process from start to finish.

The Round-Up

To reiterate the point, if after reading this guide and doing your own additional research you’re still unsure as to what to get, buy a $650-$1200 pistol chambered in .45 ACP with a Government length (5”) barrel from Springfield Armory, Colt, Smith & Wesson, SIG Sauer, Ruger, or Remington. A decent pistol from a major brand will minimize the frustration and hassles of the platform while maximizing the shooting experience.

The 1911 platform is second only to the AR-15 in modern firearms in terms of the amount of variety and options available for purchasing and customization. For the average consumer, this can present a mind boggling set of choices that may not always make sense. Hopefully this guide has helped to clarify the features and choices available.

ZAUF: The Big Three

Since we’ve covered the basic types of bullets, the next logical step would be to discuss the ‘Big Three’ of handgun cartridges.

The ‘Big Three’, as they’re colloquially known, are 9mm Luger (9×19mm Parabellum), .40 S&W (Smith & Wesson), and .45 ACP. Since this is part of our ZAUF series, we won’t go too in depth on each one, but rather cover the basics of each of them.

9mm

9mm Luger is the most popular and widespread of the three. It is the smallest round and the most common bullet masses for 9mm are 115 gr, 124 gr, and 147 gr. The ‘gr’ refers to ‘grain’ (so ‘124 gr’ would be spoken as “one twenty-four grain”), and is a unit of mass. 1 gram is the equivalent of approximately 14.5 grains.

9mm is also the cheapest of the three, currently priced around $0.21 per round for 124 gr FMJ.

Another benefit of 9mm is that due to being the smallest of the three, more rounds of 9mm can fit in a magazine of an approximately equivalent size compared to .40 S&W or .45 ACP. The examples we’ll use are the Glock 17 (9mm), Glock 22 (.40 S&W), and Glock 21 (.45 ACP), since they’re all almost the exact same size. The Glock 17 has a standard capacity of 17 rounds, compared to the Glock 22 and Glock 21, which have 15 and 13 rounds respectively.

From our subjective point of view, the recoil of 9mm feels light but snappy, and tends to cause the muzzle to flip up slightly. It’s easy to shoot out of a typical full sized or compact pistol, but gets a bit harder to handle out of sub-compact pistols.

.40 S&W

.40 S&W rides the line between 9mm and .45 ACP. .40 S&W was based off of the 10mm Auto round, but was made shorter and uses less powder in order to reduce the felt recoil when firing.

.40 S&W typically uses bullet masses of 155 gr, 165 gr, and 180 gr.

.40 S&W costs more than 9mm but tends to be cheaper than .45 ACP. It is currently priced around $0.25 per round for 180 gr FMJ.

As mentioned above, the Glock 22 fits 15 rounds of .40 S&W, compared to the equivalently sized Glock 17 (17 rounds) and Glock 21 (13 rounds).

Using our subjective view of recoil again, .40 S&W has the recoil characteristics of 9mm in that it’s snappy and causes muzzle rise, but it feels as though it has the heavier recoil impulse of .45 ACP. This makes it our least favorite of the ‘Big Three’. While it walks the middle on price and size, it feels as though it takes the worst of both worlds (of 9mm and .45 ACP) when it comes to recoil.

.45 ACP

Finally, the venerable .45 ACP was developed by John Browning in 1904, and is most closely associated with M1911 pistol. Most .45 ACP uses bullet masses of 180 gr, 200 gr, and 230 gr.

.45 ACP is the most expensive of the three cartridges, currently selling for approximately $0.32 per round for 230 gr FMJ.

One of the main complaints of .45 ACP is that due to its girth, less rounds can be fit in a magazine. As in our example of the Glock 17, 22, and 21, the Glock 21 chambered in .45 ACP holds only 13 rounds, as opposed to the Glock 17 and 22, which hold 17 and 15 rounds respectively.

Going back to our subjective recoil analysis, .45 ACP clearly has the highest recoil impulse. However, the recoil characteristics make it feel as if the gun is pushing back towards the shooter rather than flipping the muzzle up. This makes the recoil easy to control which allows for rapid reacquisition of the target. Despite the heavy recoil impulse, the characteristics of the recoil actually make it one of our favorite calibers to shoot.

ZAUF: Introduction to Bullet Types

Let’s get back to bullets. There are many different kinds of bullets available on the market today as well as a wide variety of cartridges which utilize these bullets. The anatomy of a cartridge, which we glossed over earlier, consists of 4 major components: the casing, the bullet, the gunpowder, and the primer.

Bullets come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, even within the families of specific calibers. For our introduction, I’m going to split it into 3 very general categories: Full metal jacket, hollow point, and other - since that’ll be what you see the most in stores.

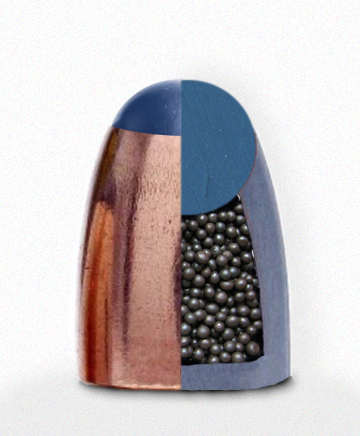

Full Metal Jacket (FMJ), as the name implies, means that the bullet (normally cast from lead [Pb]) is coated in a jacket (most commonly copper [Cu]) that leaves the base of the bullet exposed. For the most part FMJ bullets are the most common bullet types you’ll encounter on the market.

Jacketed Hollow Point (JHP) bullets are true to their name, with a hollow cavity in the nose of the bullet that exposes the lead core and allows the projectile to expand on impact, increasing the terminal damage of the projectile through soft targets. The downside of this is that against even lightly armored targets, the expansion reduces the overall effectiveness of this ammunition type.

The ‘Other’ category of ammunition covers everything from non-jacketed ammunition to extremely specialized ammunition such as Glaser Safety Slugs and snake shot (also known as rat shot). Almost all non-jacketed ammunition will lack the copper jacket the previous two categories sport and can come in a variety of shapes and purposes. For consumer purposes, these different types of specialized ammunition will become viable with experience and actual use cases.

For the examples listed above, non-jacketed reloaded ammunition can be found as an alternative to regular; Glaser Safety Slugs are a special type of bullet with a core made up of loose No. 12 birdshot capped with a polymer tip to prevent over penetration; finally snake shot (or rat shot) is fairly self-explanatory, with different caliber loads meant to be viable against snakes and vermin.

ZAUF: Types of Firearms

Now that there’s enough information to know how to read and have a basic understanding of caliber, let us move on to the firearms themselves. On the whole, firearms are split between handguns and long guns. The names themselves are fairly self-explanatory; handguns are designed to be fired in one or both hands and are generally much smaller and shorter than long arms. On the other hand, long arms are designed to be held in both hands and braced against the shoulder when fired.

Now for something slightly more technical - handguns are subdivided into two different categories: pistols and revolvers. The term ‘pistol’ implies that the chamber is integral with the barrel, meaning the term covers most modern semiautomatic handguns. Revolvers in contrast have a revolving cylinder (hence the name) which contains multiple chambers and at least one barrel for firing them. While there are other odd firearms that have been made throughout history such as revolvers with multiple barrels and multiple cylinders, they are almost completely irrelevant in a modern discussion.

The major split of long guns in the parlance of small arms (because this series won’t be talking about artillery) is between rifles and shotguns. Rifles are defined by as well as named after their rifling: lands and grooves on the inside of the barrel which impart a spin onto the bullet as it travels through. This spin (much like on an American football) gives the bullet increased stability in flight, granting an increased effective range.

Shotguns are defined by two things: the ability to fire shot shells and their smooth bore. Unlike rifles, the bore of a shotgun is generally unrifled. This is because the behavior of shot shells is unlike that of other single bullet cartridges, and rifling would have no effect on these projectiles. Shotguns have what is called a choke (either fixed into the end of the barrel or swappable) that controls the spread of the pellets as they leave the barrel.

As always, there are exceptions and combinations to these general definitions. For example, some shotguns have a revolving mechanism to hold shot shells and are technically a revolver shotgun. There are also smaller subcategories and middling firearms classified in such categories as carbines or submachine guns which are even more refined divisions of the above general categories.

ZAUF: Clips, Magazines, and You

Following the common theme of ammunition, let’s take a look at how they’re loaded into a firearm. In the early days of single shot cannons and later on hand cannons and muskets, the process was excruciating: a shooter would have to load powder in through the muzzle (the business end), tamp it down, shove a wad and bullet in the gun and tamp that down, and then use a separate trigger activated fuse to fire. Thankfully, the invention of the fully encased metal cartridges we know and love has solved all of those problems and made possible for weapons to be magazine fed.

What is a magazine? It is a container where cartridges rest before being cycled into use. A magazine can be internal or removable. An internal magazine is fixed within the firearm itself, and cartridges are added by hand or with the help of a piece of metal called a clip. We’ll talk more about clips later, but the important point is that they are not magazines. Generally, removable magazines come in a few flavors, the most common of these is the box magazine. All that means is that it is boxy and rectangular. Other types of magazines include things such as helical drums that are significantly more common on shotguns and high capacity magazines.

There are generally two types of magazines that are in common use today: Single Stack and Double Stack. What does that mean? Within the body of the magazine the cartridges rest on top of each other in either a straight line or a staggered column. The straight line resting method is called a single stack for obvious reasons, and the staggered column is the double stack. The latter method allows more cartridges to fit into a magazine because of the staggered design.

ZAUF: Introduction to Caliber

The next part of our Zen and the Art of Understanding Firearms (ZAUF) series is still part of the introduction. This entry in the series will teach you what it means when people say “.45 Caliber”, “9 millimeter”, or “12 gauge”.

With these designators, it comes down to differences between the region of origin: American vs the rest of the world. When someone says “a 45” or “45 caliber”, what do they mean? 45 of what? 0.45 of an inch, of course. So what does that mean exactly? The width at the widest part of the given bullet is approximately .45 of an inch wide in diameter. We say “approximately” because if you wanted to extend significant figures out to the thousandths place and beyond you’ll quickly realize that the measurements aren’t quite what you’d expect. In the case of .45, some 45 caliber bullets are commonly .451 inches and others are .452. Common calibers that you’ll see referred to this way are .22, .357, .45, .44, and .50. What you may also see are calibers such as .30-06 (pronounced “thirty aught six” in this case), wherein there is a hyphen followed by another number. These hyphenated numbers are completely arbitrary and their meanings range anywhere from total powder charge meant for use with the cartridge or even the year the cartridge was adopted.

In a metric world with international standards, bullets are measured using millimeters, such as 7.62x51mm and 5.56x45mm, or 7.62x39mm. What do these two numbers mean? The first number is the same as the American method of reference, meaning the width of the bullet at the widest point. The second number is the length of the casing.

So what is a gauge? Most commonly you’ll see gauge used in reference to shotshell measurements for shotguns. The real definition of what a gauge is is tangentially related to a similar density measurement of iron ball fitting in cannons that ends up being fairly obscure and technical, so we’ll spare you that aspect of it. What you do need to know and keep in mind is that usually the smaller the number, the bigger the shell, E.g. 10 gauge > 12 gauge > 20 gauge. The notable exception to this is .410 shotshell, which is measured in the American style of caliber mentioned above.

Sometimes there are cartridges that are very similar, or are slightly modified versions of each other that are designed for shooting at different pressures and will have both types of designations. Two common examples of this are .223 Remington and 5.56x45mm as well as .308 Winchester and 7.62x51mm. These two sets of cartridges are almost identical, and depending on the firearm, they will have cross compatibility. However, there are nuances I’m glossing over right now that will be explored later, so keep in mind that while they’re often interchangeable, that’s not always the case.

Zen and the Art of Understanding Firearms

There’s a Zen koan that goes,

“Nan-in, a Japanese master during the Meiji era (1868-1912), received a university professor who came to inquire about Zen.

Nan-in served tea. He poured his visitor's cup full, and then kept on pouring.

The professor watched the overflow until he no longer could restrain himself. ‘It is overfull. No more will go in!’

‘Like this cup,’ Nan-in said, ‘you are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?’”

That serves as the foundation of any introduction to Zen and Zen Buddhist philosophy. While I won’t be attempting to teach you Zen here, I do recognize the fact that for many people, starting with tabula rasa is the best way to begin any form of education: free of preconceptions and prejudice.

That in mind, let’s begin this partnered meditation on firearms. What I hope to present to you, the reader, is a guide that contains all of the building blocks to understand, operate, and master firearms in general.

So beginning with nothing, the first topic that’d be best to cover is ammunition. What do guns shoot? The correct answer is bullets, but that’s a bit of a misnomer. What you’re most likely to find on sale in stores are technically cartridges. These cartridges are collections that involve a bullet, gunpowder, and a small explosive charge called a primer all wrapped up in a metal casing. These bullets can come in a variety of forms and names, but that’s for a later discussion. Similarly not all gunpowder is created equal. Nor are the primers the same across the multitude of different cartridges. To save time, though, the metal casing only really comes in a handful of different metal types.

The most common of these in modern production is brass. You’ll find brass casings commonly in modern production ammo and it is the de facto standard of modern ammunition. The second most common of these is steel. Steel cases tend to be a sign of Soviet and post-Soviet surplus ammunition, which has its own multitude of quirks that we can discuss later. Other less common and more brand-defined metals are aluminum and a much broader and more vague term called bi-metal which, as the name implies, consists of two different metals. A special note is given to shotgun shells, which are most commonly made with plastics these days, though there are ones made of solid brass.

So what happens to this whole cartridge in the process of actually shooting a gun? Once the trigger is pulled on any given firearm, something strikes the primer, which is a contact explosive. This primer ignites and causes the powder within the metal casing to burn. The burning of the powder creates gas and pressure, which pushes the bullet out of the top of the metal casing and out the barrel.

Simple, isn’t it?